SHAPING THE FUTURE OF ANESTHESIOLOGY: Faculty Spotlight

“I have always been very determined and not easily dissuaded from goals I intended to achieve.”

Anesthesiologist and eminent researcher Miriam M. Treggiari, MD, PhD, MPH, is very deliberate in going past ifs and buts to find ways that make a difference in the lives of her patients.

“Volere é potere,” says Treggiari softly in Italian as she translates the old English proverb “where there is a will, there is a way” that has been her guiding mantra to navigate daunting research landscapes with obstinate persistence, enduring perseverance, and a whole lot of resilience. “I have always been very determined and not easily dissuaded from goals I intended to achieve.”

Curiosity, intuition, and observation push her to question current approaches and test the limits of possibilities in research work. “It is incredibly rewarding because you can see the results of your work producing a direct benefit to patients. I like to think that I have saved many more lives with my research than providing direct patient care at the bedside,” says Treggiari, vice chair for research in the Department of Anesthesiology at Duke.

Growing up near the Swiss-Italian border, Treggiari developed an interest in becoming a cardiac surgeon shortly after her father suffered a heart attack and cardiac arrest when she was just 11 years old. She resolved then that her future career would involve learning how to save him if this recurred. Interestingly, she assisted in his coronary revascularization procedure later in life. He is 88 years old and doing well, she informs with a smile.

While surgery and neurosurgery fascinated her during medical school at the University of Pavia, it was the quick thinking of the anesthesiologist “on the other side of the drapes” in the operating room (OR) that led her to choose a career in anesthesiology. Treggiari was particularly attracted by the critical care environment and energized by its intensity, the variety of clinical conditions, the challenges of problem solving, and the comprehensive nature of the medical knowledge involved. “It was the ability to see intervention and its effect, the diversity of the situations, and the intellectual stimulation that I found most rewarding,” she adds.

Treggiari’s research career started with unexpected success during a medical student exchange program sponsored by the European Community’s ERASMUS Program. With no prior research background as a medical exchange student at Ninewells Hospital and Medical School in Dundee, Scotland, she set up a project to study the recurrence of esophageal strictures and their predictors, collect data, analyze it, and write a manuscript.

“I really didn’t know much about conducting research; I was just following instructions. I presented the data to the statistician and looked over his shoulder as he ran the code for the statistical analysis on an old-frame computer. I can still remember the excitement when we discovered that we had identified an important predictor of esophageal stricture. It was an exciting and thrilling moment the first time I made a contribution, albeit small, to the scientific community.” The ability to answer a question convinced her to do research for the rest of her life, informs Treggiari.

How to Lead in Research

Be passionate

Be open-minded

Be a good listener

Be a self-starter

Be resourceful

Be resilient

Be rigorous

Be a role model

Be a finisher

The guidance of extraordinary mentors shaped Treggiari’s academic trajectory. During her residency, Dr. Peter Suter, dean of the School of Medicine in the University of Geneva, channeled her research path forward. She was selected in a scholar’s program (Programme de Relève Académique) established for the career development of future academic leaders, especially women, to address the imbalance of leadership positions that then favored men, she informed. Concurrently, Treggiari learned cardiovascular and respiratory physiology from giants in the nascent critical care environment in Europe, including Suter, founding father of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and Dr. Jacques-Andre Romand, a renowned anesthesiologist and intensivist.

Her thirst for knowledge widened her geographic and academic horizons. After residency in 1999, Treggiari earned a second Swiss Medical Doctor degree in Geneva and headed to the United States as a visiting scholar in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Washington (UW), Seattle. Five board certifications, an MPH in public health, a PhD in epidemiology, and several exams later, Treggiari focused on gaining valuable clinical work experience. She served as professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine with adjunct appointments in the Department of Neurological Surgery and the Department of Epidemiology (2011-2014) at UW, endowed professor and vice chair for research in the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University until 2019, and a tenured professor and vice chair for clinical research in the Department of Anesthesiology at Yale University.

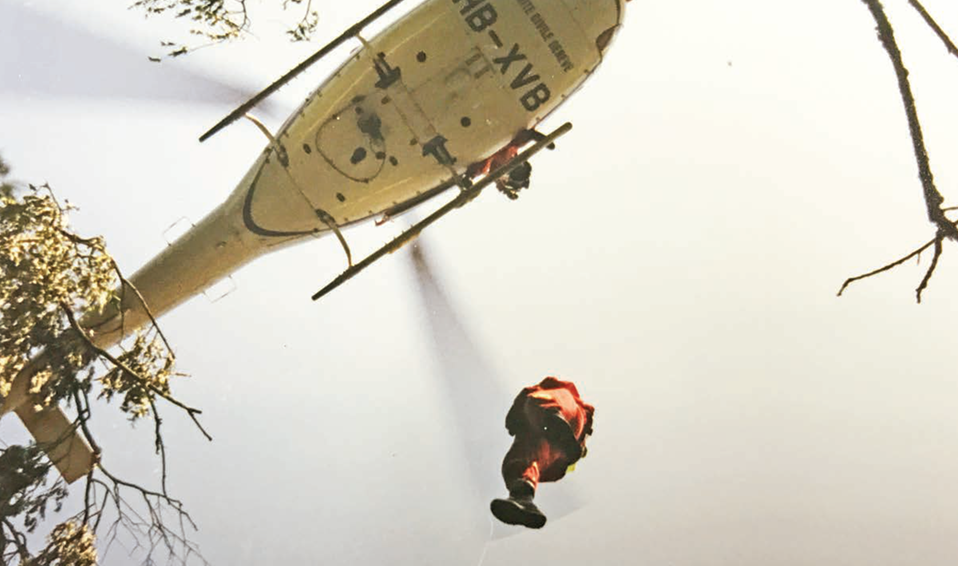

“Helicopter rescuing was exciting and extremely intense. It required preparing for the unexpected, real-time problem solving and fast thinking. I learned about emotional intelligence and how to think outside the box in very challenging scenarios. There are no limits to what we can accomplish.”

In 2022, Treggiari joined Duke Anesthesiology inspired by the diverse research programs from basic science to population health, its prominent scientists, and a strong commitment to academic excellence. A dedicated researcher in clinical and outcomes research, she envisions carrying forward the rich legacy of her predecessors and taking the department’s research endeavors to the next level. Among her goals is to bring the late Dr. David Warner’s unfinished work on antioxidants and brain ischemia to completion. She also plans to help restart the late Dr. William Maixner’s drug discovery program in the Centers for Translational Pain Medicine and Perioperative Organ Protection.

Excited to work in an environment especially supportive of junior faculty, Treggiari plans to ensure both opportunity and resources for those committed to the success of Duke Anesthesiology’s research mission. She aspires to make Duke Anesthesiology the best research program in the country with a focus on drug discovery and development of new therapies for pain and stroke. “We are growing our translational and clinical research footprint incorporating novel research methods based on either mechanistic or pragmatic approaches. We will also grow new clinical trial programs in partnership with the Duke Clinical Research Institute.”

The Road to Leadership is Mentorship

Explore and seek out great mentors, and establish strong relationships with them. Mentorship relationships start with a mutual connection and are built on trust and mutual respect.

Direct, honest, actionable feedback is of huge value, although it may not always be perceived that way. Be open to accept the feedback and use it as an opportunity to learn, grow and increase your self-awareness.

It takes time and energy to develop a mentee, and it is necessary to be accessible/available and allow time to give input and to monitor progress. Have clear expectations and rely on milestones and timelines to stay on target and to revisit goals as needed.

Mentors can also be sponsors that advocate and identify opportunities for their mentees through opening doors and investing in their success (e.g., employment recommendations, networking, etc.).

Early career physicians/scientists, women in particular, should be encouraged and prepared to assume leadership roles by enhancing their self-awareness and realization that these opportunities are within their reach. Preparing leaders to assume such roles will help shape a strong and rich future for anesthesiology.

Funded through federal, foundation, and industry support, Treggiari has brought about a paradigm shift in the medical practice guidelines for critically ill patients, both nationally and globally. Not afraid to challenge traditional dogma, Treggiari’s research has deeply influenced critical care management from sedation and hemodynamic management to glucose control. In the early 2000s at UW, Treggiari made an important observation that critically ill patients who were routinely given deep sedation during mechanical ventilation were more likely to experience complications like delirium and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Consequently, Treggiari presented an evidence-based systematic investigation that would later change culture. “It was a very odd concept to introduce that it’s okay for a patient to be awake while being mechanically ventilated,” she added. Her work contributed to a profound change in the approach to ICU sedation for mechanically ventilated patients. Adopted first in UW, it soon influenced ICU sedation practice worldwide.

Treggiari’s work has highlighted the potential negative effect of interventions related to hemodynamic management and fluid administration in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. “We first demonstrated this in a metanalysis that was published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, and then a pilot study that was published in Neurosurgery.” She was then invited to join the international consensus conference panel to recommend medical management guidelines of subarachnoid hemorrhage that are now followed globally. “The updated guidelines have been recently published in Neurocritical Care,” informs Treggiari, adding that these guidelines have been endorsed by societies, including the American Heart Association, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, among others.

In an observational study on 10,000 patients in the early 2000s, Treggiari’s team showed no improved outcomes with tight glucose control, thereby refuting an earlier study that had indicated benefit. Her findings, confirmed by subsequent studies, led to a global unanimous decision to abandon the tight glucose control approach in critically ill patients, and revert to standard glycemic control practice. Treggiari’s work on ICU organization and structure has received national media recognition.

Her roles—as a clinician in several ICUs and ORs, an administrator as vice chair for research, and as an internationally recognized researcher with more than 150 peer-reviewed articles in high-impact journals to her credit—all work in harmony to enhance patient care.

Navigating Your Research Pathway

Passion: Good research requires hard work, self-determination and takes time. New investigators should consider research areas that they have a passion for; it is far easier to spend time working on something that inspires you than working in areas that do not.

Perseverance: There is great satisfaction when projects are successful, and you see the impact of your work on advancing science, practicing change or improving care, but there will invariably be challenging times along that path. However, there is typically more than one way to solve a problem.

Focus: It is important to stay focused on the overall objective and not be discouraged by the unexpected disappointments. It helps to keep an open mind and to remember the big picture.

Opportunities: Chances for growth and enrichment are all around us. Recognize meaningful opportunities and prioritize in steps so that the tasks will not be overwhelming, and the opportunities will not be lost.

Hard work: “I genuinely believe that hard work – exceptional hard work – is the key factor to succeed in medicine.”

While Treggiari chiseled a roadmap for success through methodological rigor, she also made mistakes and learned from them. As a resident in the mid-1990s, she conducted an ambitious study following the excitement in the anesthesia community about the newly discovered pulmonary vasodilator, nitric oxide. “There was really no experience of human exposure, therefore we collected extensive data showing that not every patient improved when exposed to this agent.” However, her study was initially rejected by prominent journals citing methodological flaws. Although disheartened by these rejections, Treggiari humbly recognized that her data were complex and had limitations.

“Occasionally, failure is to be expected. Learn from failures and move on,” she stresses. She advises researchers to adequately plan, adhere to methodological rigor, break down long-term goals into bite-sized achievable steps, and pivot in the face of roadblocks.

Her goal is to customize learning for researchers to address gaps upstream and prevent problems downstream using existing resources at Duke. “There’s a shift to grow stronger mentors and introduce the concept to mentoring early on in careers,” says Treggiari. “Most of my mentors have been men,” she adds, emphasizing the need for diversity with more women and minority mentors to foster a better mutual relationship with young researchers. At Duke, she appreciates the ongoing efforts to develop and grow a diverse group of leaders.

Treggiari sees the field of anesthesiology evolving dramatically over the next decade. “We can envision patient care in the OR where we will no longer have cords or cables and patients will arrive to the room with their wearable devices placed preoperatively. Telemedicine will replace most in-person visits and patients will be monitored remotely. Surgeries will become less and less invasive. Large data-driven research and pragmatic trials will replace traditional placebo-controlled trials. Precision medicine with endotyping of subpopulations will become part of usual care and providers will need to rely on artificial intelligence (AI) tools for decision support for patient care to implement personalized approaches.”

While working in high-acuity environments drives this physician-scientist to scale new heights, her family keeps her grounded. She cherishes spending time watching her daughter, Sofia, ride a horse they just acquired, or cheering on her son, Malcolm, as he competes in a Carolina Junior Hurricanes game. Getting in a competitive game of tennis with her husband, David, on a sunny winter day helps Treggiari recalibrate her personal and professional roles. “I plan my life in a very deliberate way and arrange my life around things that I need to do,” she says, as she looks for the next big thing in research.