On March 30, we (members of Duke Anesthesiology) left Durham to participate in Extreme Everest 2017, a scientific expedition to the Everest base camp and Kala Patthar in the Himalayas. This had been organized by a British team, including Professors Monty Mythen and Mike Grocott, who had summited Mount Everest and performed numerous groundbreaking studies in 2007 and 2013. In the current expedition, we headed for Nepal for the second time, this time joined by a Duke Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (UHM) fellow, Dr. Chris Martin, and former Duke UHM fellow, Dr. Nicole Harlan, along with Dr. Joe Wiater and Fran Cullen, a financial advisor in Durham. The aim was to trek from Lukla to Everest base camp over 11 days, while measuring pulse oximetry continuously in a cohort of 14 individuals.

Why do this? What can be achieved from an observational study during the field expedition? The answer is that no one knows the lower limits of acceptability on blood oxygenation. While tens of thousands of individuals have trekked to Everest base camp without a problem, their oxygen saturation values have largely been unknown. Several studies have incorporated spot measurement of SpO2 but no published studies thus far have measured it continuously. In 2013, we obtained some data using wrist oximeters; the plan this year was to extend those studies.

Our team flew to Kathmandu, arriving on March 31. Among the 46 members of the group, several were doing research projects. These included an investigation of the microbiome and echocardiography at three different altitudes. Another investigation was looking for antigens that might explain the ubiquitous ‘Khumbu cough’ as due to inhalation of aerosolized yak dung particles. For our study, we signed up a number of the trekkers and obtained overnight baseline measurements. On April 3, we made our way to Kathmandu airport for the 40-minute flight in a Twin Otter aircraft to Lukla, altitude 9,317 feet. The Tenzing-Hillary airport at Lukla is reported to be the most dangerous airport in the world because its unique runway is positioned between two cliffs which leaves no room for error on landing. However, we landed safely and after gathering in a coffee shop for a brief refreshment, we headed up the mountain toward Monjo. Hiking in North Carolina can be challenging, but it is nothing like this. Unacclimatized as we initially were, dyspnea was a constant accompaniment. After several hours of hard trekking, we reached Monjo in the dark, and the next day to Namche (altitude 11,283ft), where we spent three days. Glancing periodically at our pulse oximeters revealed measurements that were consistently in the 70s. Apart from the shortness of breath, we felt fine and were able to carry on up the trail. Namche is a small town and would be the last ‘comfort stop’ on the way to base camp: there were coffee shops, lattes and just about anything you might need to buy for the remainder of the trip. The guest house where we stayed was owned by a man who was completely deaf due to meningitis as a child. However, he was a brilliant lip reader and an even more brilliant photographer. He plans to use proceeds from the sale of his photographs to fund a museum.

After our mandatory acclimatization, we headed up the trail toward Debouche (altitude 12,369 ft) and then Pheriche (14,010 ft), where we spent three nights, again to acclimatize. Pheriche is the site of the Himalayan Rescue Association, a bare bones facility but regularly and effectively staffed by doctors from around the world. Although most of us felt okay, medical problems started to occur. The first was one of our co-trekkers who abruptly lost consciousness while sitting outside a teahouse waiting for lunch. A couple of days later someone on another trek was visibly ataxic as he walked along the trail. The diagnosis: high altitude cerebral edema – HACE. Dr. Chris Imray, one of the British medical leaders, administered dexamethasone, walked with him to a helipad and escorted him back to Kathmandu by helicopter. Later, two of our group members would suffer HACE themselves. Fortunately, in all instances, dexamethasone and descent did the trick.

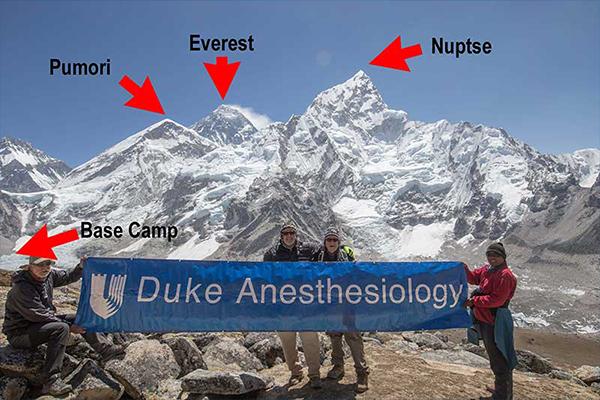

Gorak Shep (altitude 17,126 ft), the original base camp for the Hillary-Tenzing expedition in 1953, was our last stop. The day after our arrival there, most of the group trekked on to the current base camp at about the same altitude. The two of us, along with four other trekkers, including Chris Imray and Jeet Sherpa, hiked up Kala Patthar (altitude 18,519 ft). The prize on this mountain is a spectacular view of four peaks: Everest, Pumori, Lhotse and Nuptse. Although we didn’t quite make the summit due to incoming inclement weather, we did get the view and a backdrop for the Duke Anesthesiology banner. The climb nevertheless was tough, and my pulse oximeter was reading its lowest value of the trek: in the low 60s.

The next morning was the planned start of the descent. Before heading down, several of the trekkers set out at 5 a.m. to climb Kala Patthar. We and the British medical leaders had waited until their return before setting out. Unfortunately, as it turned out, one of our trekkers returned with a case of HACE. It would have been impossible to evacuate by helicopter as it was snowing, so she was given dexamethasone and allowed to sleep. The cure was miraculous: a few hours later she and her doctor, Dan Martin, zoomed past us on their way to the next stop at Loboche.

The downhill trek seemed uneventful until we were a few hours past Dingboche. As we walked through a small village, we were debating whether to stop for coffee when we spotted a few of our fellow trekkers. In the end, we decided to sit down with them to enjoy a few minutes of rest, but a few minutes later we heard someone yelling for help. Both of us, along with Aine Burns, a London nephrologist, and her daughter Brid, a medical student, rushed up the trail as fast as we were capable, where we found a man lying on the ground. The sherpa who had been accompanying him reported that he had not felt well earlier in the morning and had been advised to hike slowly. Abruptly, he had fallen down, unconscious. Fortunately, Nima (our Sherpa) had the medical kit with which we were able to check the man’s glucose to exclude hypoglycemia and then administer IV dexamethasone for presumed HACE. The stars had lined up for this man as a Nepali Army platoon was hiking through the village and was able to request a helicopter and carry the man up the hill for evacuation.

That night was spent at Tengboche, then we headed to Namche and then Lukla followed by the short hop back to Kathmandu.

What about our study? The data is being analyzed, but we had clearly observed that normal hikers trekked at altitude for long periods of time at SpO2 values, which if seen in any of our hospital patients would elicit panic.

However, it was great to get back to normoxia where we could climb stairs and walk up hills with relative ease. We hope that the eventual publication, which might be entitled, “Oxygen saturation: How low can you go?” will elicit conversations as to alternative strategies for treating hypoxia in patients.

By Drs. Richard Moon and Eugene Moretti