GLOBAL HEALTH: Blogs from Abroad

GHANA: Making a Difference 5,365 Miles from Durham.

Fintan Hughes, MBBCh, BAO | RESIDENCY CLASS OF 2024

Intensive Care Unit

In September of 2023, we traveled to Accra, the capital city of Ghana in West Africa. Our main roles during the trip were to assist Dr. Adeyemi Olufolabi in establishing the use of labor analgesia and to teach local residents about neuromuscular monitoring and video laryngoscopy. We were primarily based at the newly-opened University of Ghana Medical Center (UGMC).

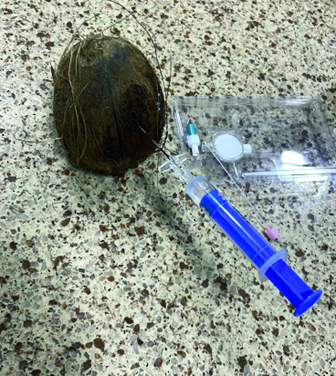

We worked alongside Dr. Olufolabi, teaching UGMC residents the skills required to place epidural catheters. UGMC has a simulation center with an excellent model for neuraxial placement, but to facilitate widespread access to simulation we experimented with a variety of items from a local market. After much trial and error, we found that a coconut with holes drilled through the outer husk provides a crisp loss of resistance as a Touhy passes from the white flesh into the hollow liquid filled inner space. Pineapples were a close second when the Touhy was advanced from the base, but became much less consistent as the fruit ripened.

We delivered lectures to the anesthesia residents on the monitoring of neuromuscular blockade. Additionally, we gave tutorials on emergency airway management to the residents and nurses. Day-to-day in the operating room, we demonstrated the practical use of both train-of-four monitoring and video laryngoscopy.

A highlight for me was the simulated cardiac arrest sessions that we ran in the Intensive Care Unit. Navigating the culture’s differences while practicing closed-loop communication led to a lot of laughter all around. This was all made a little more exciting as we used a live defibrillator at 4 joules rather than a training unit.

It was fascinating to see two very different approaches to global health work being undertaken in Ghana. During our time at the hospital, we met a cardiac team from another US academic center. The primary aim of this group was to complete a large volume of surgeries in their time in the hospital. While this well-oiled machine provided excellent care to many patients, their work was met by local staff with varied responses. This is a completely different philosophy to Dr. Olufolabi’s capacity building model. Capacity building in global health seeks to develop long-running partnerships with local doctors and nurses. Listening and responding to the needs of local health care workers, both sides collaborate to develop sustainable solutions, and in time, the local teams become independent.

This trip was an inspiring window into the vast need for effective global health work that exists even in the more developed countries of the global south. BP

Keith VanDusen, MD | RESIDENCY CLASS OF 2024

I recall feeling apprehensive as I embarked for Accra, Ghana, where Bert Cortina, Fintan Hughes and I spent four weeks on a global health rotation under the mentorship of Dr. Adeyemi Olufolabi last September. As outsiders entering an unfamiliar medical system, we didn’t know what to expect. Would we be embraced or mistrusted? Could we provide meaningful service, or would we be a distraction?

What followed was the most formative month of my residency training. We spent most of our clinical time at the University of Ghana Medical Center (UGMC), where Dr. Olufolabi taught neuraxial techniques to enhance its obstetric anesthesia program. Throughout the rotation, we gave lectures, assisted with cases, and learned to conserve resources when administering anesthesia. We also toured public hospitals and explored the study of global health more broadly with an emphasis on program development, outcomes assessment, and sustainability.

While these clinical and academic pursuits were uniquely educational, the opportunity to experience Accra proved even more valuable. Dr. Olufolabi encouraged us to visit museums, restaurants and civic landmarks. He brought us to the historic Jamestown district, where we explored a community-run school, searched for street art, toured a boxing gym, and learned about ongoing exploitation of the area’s limited resources. He led us through the dense Makola Market, took us on a weekend road trip, and even convinced us to go dancing. He also showed us the Cape Coast castle, which provided a harrowing look into the region’s prior slave industry. Throughout the trip, Dr. Olufolabi served as a full-time guide, driver, historian, and mentor. This surely was exhausting for him, but it provided an incredible experience for us.

Beyond even the history and culture we experienced, it was the people we met in Ghana that made the trip truly unforgettable. Dr. Olufolabi’s colleagues and friends welcomed us into their homes, prepared meals and offered gifts. Even the UGMC staff, whom I worried would consider us a distraction, have kept in touch via text and social media. The warmth with which they invited us to learn about their lives, careers, and country stood out among the highlights of our rotation.

Our rotation in Accra was easily the most important month in my residency training. It was a perspective-altering experience, and I’m sincerely grateful to my co-residents, both those on the trip and those covering shifts while we were away, our department for sponsoring the adventure, our numerous hosts in Ghana, and, of course, Dr. Olufolabi, who enabled every part of the adventure. BP

George Cortina, MD, PhD | RESIDENCY CLASS OF 2024

Opportunities during residency to expand one’s training outside of their own institution, much less the country, are rare. When applying to Duke Anesthesiology, I heard about the global health rotation and, as a CA-3, had the fortunate chance to join Dr. Adeyemi Olufolabi on a rotation in Ghana. These four weeks proved to be some of the most valuable for my training.

In the days before leaving, I had a general sense of the intended goals, but upon arrival, I realized that much like language immersion, experience is the most effective teacher. Most days were spent at the University of Ghana Medical Center (UGMC), but every day varied. One constant was our work with and teaching of anesthesia trainees. The spontaneous conversations throughout the day, where we traded insights, taught both of us the most. Ghana is resource-limited, but UGMC had received some newer equipment not available in many hospitals in the country. Often, it was the trainees’ first experience with such equipment, and they would come to us with questions about it and seek advice about care. We set up a series of both lectures and informal sessions. The most popular was a mock code we designed, where we emphasized crisis communication just as much as advanced cardiac life support. Throughout the days, they also demonstrated how they approached many of the same challenges that we face in the OR with limited resources. One thing that struck me was their adaptability and commitment to training and medicine.

Most importantly, we built friendships and connections that continued even after we returned. Everyone was proud to welcome us to Ghana and share their culture. They invited us to their houses, shared incredible food, and took us to their favorite places in Accra. Their passion for medicine, in the face of several systemic challenges, was inspiring. These great experiences provided context for our learning and teaching at UGMC, enhancing the depth of our engagement. This was a life-changing introduction to global health that has provided a background for getting involved in similar initiatives later in my career. I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to have been a part of this rotation. BP