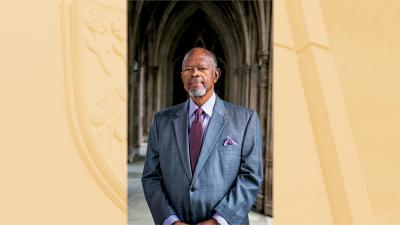

Alumni Notes: Q & A with Sir Winston CV Parris, KCSL, CMG, MD, FACPM

A one-on-one interview with Dr. Winston CV Parris, an internationally-renowned pain medicine specialist and clinical researcher recognized for the development and historic launch of a non-opioid topical analgesic and awarded a knighthood for his contributions to the specialty.

Q: Why anesthesiology?

A: I was intrigued with the principles and science of producing “sleep for surgery” while simultaneously maintaining the satisfactory integrity of other bodily systems. It also occurred to me that St. Lucia, my country of birth, never had a local anesthesiologist. In an attempt to correct that deficiency, I completed the anesthesia training program at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica and returned to St. Lucia in 1971 where I served as the only anesthesiologist on the island for nearly five years.

Q: How did your experience in St. Lucia help to shape your career?

A: Knowing that there would be no one to collaborate with nor to give me any clinical support, I was filled with initial trepidation; I had to mature very quickly and develop the confidence that was necessary to execute the skills to run that service in our hospital. It also provided me with the humility to recognize my limitations in certain subspecialties, which led me to seek additional training at Vanderbilt University in 1975.

Q: What attracted you to the field of pain management?

A: I was fascinated with the administration of epidural anesthesia, and I spent a good deal of time learning and perfecting that skill in the obstetric suites. This new-found experience permitted me to try a variety of nerve blocks at a time when these procedures were seldom used. I was frequently asked to do various interventional pain procedures for patients with intractable chronic pain. I remember doing a celiac plexus block (without fluoroscopy) for a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer and observing their remarkable pain relief. I voiced at that time that it appeared to be futile to repeat the same surgery for back pain on a patient multiple times. Leadership agreed, and that is how the Vanderbilt Pain Management Center was born—the first pain center in the state of Tennessee—with me as its medical director.

Q: Key lessons from your leadership roles?

A: In the process of establishing a multidisciplinary pain control center at Vanderbilt University and also establishing pain centers in diverse parts of the world as president of the WSPC, while dealing with multinational and multicultural personalities with diverse habits and egos, the following lessons stand out: the need for thorough planning, meticulous organization, patience, humility, and the need to learn to “listen more than you speak.”

Founding member

American Academy of Pain Medicine; American College of Pain Medicine; American Board of Pain Medicine; Tennessee Pain Society

President

World Society of Pain Clinicians (WSPC); helped develop pain clinics in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Far East, and Eastern Europe

Founding medical director

Vanderbilt Pain Management Center

Chief

Pain Medicine Division

Duke Anesthesiology

Earned the Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) for his service and accomplishments in the field of pain medicine

Received the St. Lucia Cross

for his contributions in pain medicine

Awarded a Knighthood (Knight Commander of St. Lucia) on the recommendation of the Prime Minister and government of St. Lucia, with the approval of the late Queen Elizabeth II

Completed the clinical trial of Bonipar and the product development of Fidapin—two topical analgesics

Q: Key qualities of a good mentor?

A: In my humble opinion, the following qualities are critical: 1) patience, 2) disciplined tolerance, 3) meticulous planning, 4) trust and understanding that people have different personalities and diverse interests, 5) meaningful communication, 6) compassion, fairness and integrity, and 7) the ability to motivate especially the ‘not-so-gifted’ mentees and to recognize when “one is not having a good day.”

Q: At what point in your career did mentorship most influence your path?

A: The late Dr. Bradley E. Smith, professor and chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at Vanderbilt, was by far the most important mentor in my anesthetic career. He admitted me into the anesthesiology residency program in 1975 at a time when people who looked like me were seldom seen in white coats. In fact, I was the first Black anesthesia resident and the second Black resident in the Vanderbilt Medical Center. I was grateful to observe that Brad’s bold moves have helped to open the door for other department chairs to diversify their residency programs. He was also very supportive of my bold plans to establish the first pain center in Tennessee.

Q: You have published extensively on the anesthetic management of many complex diseases. What is your advice for early career physician-scientists looking to navigate the research environment?

A: My advice is to develop and aggressively practice intellectual curiosity whenever possible and to learn to collaborate with other colleagues, within and outside of one’s own department. And if possible, this collaboration could extend to other institutions and when practical, to other countries. It is also important to recognize that procrastination is never your friend.

Q: You are credited with developing a protocol for the anesthetic management of systemic mastocytosis. How did this discovery impact you as an anesthesiologist and researcher?

A: My early exposure to this condition heightened my sensitivities in preoperative evaluation and also in paying close attention to patients’ past history of anesthetic complications. That sensitivity allowed me to identify those cases preoperatively rather than intraoperatively, and also allowed me to develop alternative methods for the induction and maintenance of anesthesia for patients with systemic mastocytosis and related disorders. Systemic mastocytosis results in the massive release of histamine when various intravenous anesthetics, muscle relaxants, sedatives, and other drugs are administered in those patients during anesthesia. The net result of those injections is a significant development of tachycardia and severe hypotension followed by cardiovascular collapse, which if not treated promptly, could usually result in death. The best way to treat systemic mastocytosis is to avoid its development. This can be best done by avoiding most intravenous agents and adopting the good old-fashioned inhalational halogenated anesthetic agents for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. Preoperatively, meticulous skin tests can identify those patients who might develop severe complications during anesthesia.

Q: What publication are you most proud of?

A: My publication on the anesthetic management of systemic mastocytosis is very dear to me. Prior to my publication, this condition was frequently associated with perioperative death. It has been very rewarding to learn that many anesthesiologists have followed the clinical recommendations proposed in my paper. I still receive phone calls from physicians all over the world requesting assistance with some intraoperative difficulty in the anesthetic management of patients with that condition, and it is gratifying to know that my publication was of assistance to those patients.

Q: What are some critical steps in advancing science in general?

A: I think some of the critical steps include data collection and intermittent review of that data, intellectual curiosity to always ask questions (no matter how ridiculous they might at first appear to be) and attempting to seek answers or solutions to the problems, meticulous observation of anomalies or unusual phenomena, and utilization of sophisticated or even unusual methods to attempt to connect basic science with clinical practice.

Q: Since retiring from clinical practice, you’ve been actively involved in research and clinical trials of topical analgesics for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain syndromes. What is your advice for a successful clinical trial?

A: Prerequisites for a good clinical trial include preparation of a sound protocol with good clinical methods, a reliable and competent statistician, and a good team to help execute that clinical trial. Since most physician anesthesiologists taking on clinical trials also have clinical responsibilities, it is imperative to have an individual or team to assist in communications with the IRB for getting approval of the clinical trial and for interacting with the FDA in facilitating an IND, if necessary. One should also clearly determine the cost and funding for the clinical trial.

Q: How did your time in academia and private practice aid in your product development?

A: My academic background and the business and medical political experiences that I gained in private practice prepared me to successfully approach this new challenge with confidence and positivity. My interest in product development evolved after I retired; I spent winters in my island home of St. Lucia, and it was during one of my trips there that I became intrigued by the use of local coconut oil and related oils for treating a variety of ailments, including chronic pain syndromes. Intense evaluation and research of those essential oils precipitated my successful clinical trial and subsequent development of the topical analgesic, Fidapin. Earlier this year, I completed a clinical trial at Duke Anesthesiology on a second generation of topical analgesics, called Bonipar.

Q: What is your viewpoint on product development/partnering with industry?

A: Since the issuance of my product patents from the US Patent and Trademark Office, I have been inundated with requests for partnership from various venture capitalists. I have steadfastly avoided any such relationships because although initially the financial assistance would be wonderful, my best instincts are to maintain my independence. However, I plan to work with suitable pharmaceutical companies to assist me in the development and launch of Bonipar.

Q: What are the critical steps to be successful in the realm of clinical research?

A: In my opinion, the steps include a critical assessment of current clinical methods and the intellectual curiosity to understand the fabric of those methods and also to try to improve on those methods; a desire to correct any unfavorable outcomes and if necessary, to try to establish protocols to prevent them; to try to link various clinical methods with the basic sciences and hopefully evolve new methods; and to be open to new ideas and criticisms from other sources.

Q: How have you been able to sustain such a productive career spanning decades?

A: I have been blessed with good health, a reasonably good memory and the capacity to require very little sleep; I believe that combination contributed a great deal to the success in my career. Nevertheless, I would give credit to my late mother, my late wife, and my current wife, whose nurturing, love and care created the environment and the sustenance that made any modest accomplishments of mine possible. My family has provided me the strength, the stability, the endurance, and the ambience to be able to think clearly and to work hard. I am eternally grateful to all of them and of course, to the Almighty God who made it all possible.

Q: What is your philosophy on work-life balance?

A: My late mother used to say to me, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” Most of the time I have listened to my dear mother. Through much of my life, I’ve played tennis, and now, I golf multiple times a week. I believe that regimen of activity helped not only to keep me physically fit, but it also helped clear my mind of any potential distractions which might otherwise interfere with my daily routines. Thus, I think it is critical to have some outlet, preferably physical, to serve to optimize the work-life balance that is necessary to have great success in one’s endeavors.

Q: What is your best advice to those looking to enter the anesthesiology specialty?

A: With the passage of time and the physical rigors of this specialty, one can opt to focus on a subspecialty and get tremendous satisfaction in the process. Although the administration of general anesthesia provides the cornerstone training for the management of patients undergoing surgery, that process exposes you to the various horizons that may fulfill your innate passion and ambition. Those with a basic interest in pharmacology, cardiorespiratory physiology, and the central and peripheral nervous system, can easily fall in love with the specialty and appreciate the wise words, “Eternal vigilance is the price of safety.”

Q: Last year, the key word in “Alumni Notes” was bravery. What would you say is the key word of your journey?

A: My suggestion for 2023 is CURIOSITY.