TRANSFORMING THE FUTURE OF Critical Care

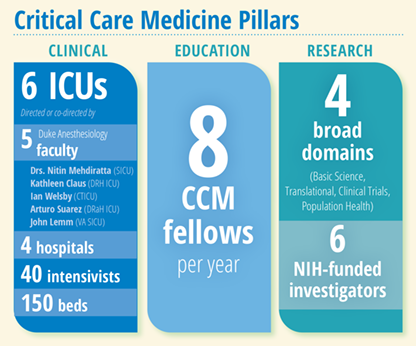

Intensivists come to work every day in six intensive care units (ICUs) across four hospitals guided by one shared purpose - to improve the lives of critically ill patients at Duke and around the world. They weave compassionate humanity and detailed medical knowledge into the fabric of critical care medicine and provide high-quality, data-driven, and equitable clinical care for patients facing life-threatening illness or injury.

They know that care for the critically ill cannot be delivered alone. It is a symphony of exceptional leadership skills and strong teamwork of health care providers that work in concert to build trust with patients and their families and help them navigate through a host of decisions, emotions, and choices, including end-of-life discussions.

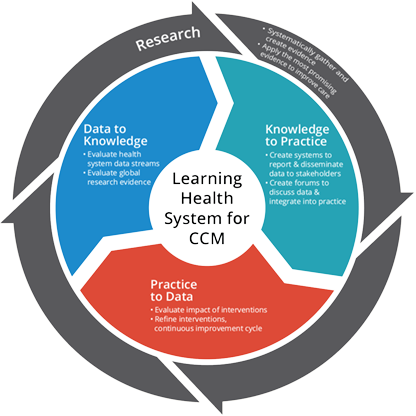

The focus, says the new chief of the Critical Care Medicine Division, Vijay Krishnamoorthy, MD, MPH, PhD, is on “developing a ‘learning health system’ where science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the care delivery process - ultimately keeping patients and their families at the center of everything we do.”

Under the dynamic leadership of Krishnamoorthy, appointed division chief in February of 2022, Critical Care Medicine at Duke is well-poised in realizing its vision to discover, deliver, and transform the future of critical care and become a world leader in this niche domain.

Krishnamoorthy has ambitious strategies to engage all stakeholders for expanding Duke’s critical care footprint well beyond its brick-and-mortar walls, especially in the clinical operations and learning health, research, and education domains.

Critical Care Medicine INNOVATIONS

Duke ICU Universe | Duke Health ICU Collaborative | Building Learning Health System for CCM | Population Health in Critical Care through CAPER | Integrated Research Programs | Collaborative, Personalized Educational Initiatives | Tele-ICU Approach to Expand Clinical Footprint

The main principles that underscore all efforts are innovation and collaboration. Krishnamoorthy meets every week with his core leadership team (Nitin Mehdiratta, MD, clinical operations director, and Nazish Hashmi, MBBS, fellowship program director) and quarterly with all six ICU medical directors, to discuss innovative care processes, adopt best practices to improve patient outcomes, and keep efforts collaborative across various ICUs. Additionally, an annual retreat of the leadership team (comprising Mehdiratta, Hashmi, and all ICU medical directors) is held to develop broader strategic goals for the division.

As part of his clinical strategy (Figure 1), the team captures new knowledge through data derived directly from the delivery of care, informs Krishnamoorthy. This data is transformed to become knowledge to help implement the best evidence into daily practice. The loop is complete when clinical practice improves and continues to capture data and inform subsequent management. “Through our informatics systems, we are able to capture data, evaluate it rigorously, and use it to optimize and innovate our practice,” adds Krishnamoorthy.

At the heart of this strategy is the Duke ICU Collaborative and the “ICU Universe,” conceived to collect and curate the entire critical care data generated across all ICUs in the Duke University Health System (DUHS) in Epic, the electronic medical record. “The data updates every midnight giving both historical and contemporary information to critical care teams,” informs Krishnamoorthy. The Duke ICU Collaborative helps to operationalize the “learning health system” and represents key stakeholders across all ICUs in the health system who work together to review data, share learnings across ICUs, and implement best practices. The Duke ICU Collaborative learning health system activities include: 1) a weekly summary of global evidence shared with providers to update them and encourage discussions on ways to optimize evidence-based practice and reduce variation in the processes of care; 2) a monthly learning health collaborative newsletter; 3) a quarterly learning health conference (to review Duke ICU data and share best practices) as part of CCM Grand Rounds; 4) a quarterly ICU quality improvement committee discussion about case learnings, strategic implementation, and outcomes of improvement projects; and 5) rigorous research to evaluate the outcomes of interventions conducted across ICUs.

Information is developed and shared in a variety of ways. A WhatsApp forum provides a platform for faculty across ICUs to engage in informal (non-PHI) discussions surrounding evidence and best practices, while the quarterly learning health care conference (organized with Mehdiratta and pulmonologist, Daniel Gilstrap, MD) disseminates lessons learned from captured data and evaluates the impact of interventions. Local ICU data is also shared with medical directors for discussion in their respective faculty meetings.

Co-leading the Duke ICU Collaborative Quality Improvement Committee, Mehdiratta ensures that safety and quality of critical care services are maintained in six ICUs with 150 critical care beds across DUHS. “I am trying to create a more cohesive QI Committee throughout the hospital system.” He employs the “Plan, Do, Study, Act” strategy to identify problems and develop and implement workable solutions in clinical practice, while monitoring the transition of knowledge to practice. Participants, including physicians, advance practice providers, and nurses, work together to achieve this goal.

Mehdiratta implements evidence-based strategies to see change happen in real time. One example of this tangible outcome is the central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) project, first implemented in 2021 in the Surgical ICU. With a multipronged approach, “we were able to reduce our CLABSI rates within one year, and we subsequently went without a single CLABSI for over 400 days,” he says proudly. Mehdiratta, along with his team (Staci Reynolds, Brandie Slagle and Christopher Sova) were awarded the Karsh Award for their outstanding work on reducing CLABSI rates in the SICU in 2022. They have received health system-wide accolades for their efforts in reducing hospital-acquired infections.

Along with his focused QI efforts, Mehdiratta is making concerted efforts to improve workflow by creating a robust training and education process for a standard of care practice that can be successfully replicated to improve patient outcomes across the entire spectrum of critical care at Duke and beyond. As part of the CCM Fellowship, all eight fellows are required to complete quality improvement projects, coordinated by a designated QI fellow every year, informs Mehdiratta.

The CCM Division’s footprint in research is expansive and covers areas “from the level of the cell all the way to an entire population,” says Krishnamoorthy. For the population-level impact, Krishnamoorthy highlights the role of the Critical Care and Perioperative Population Health Research (CAPER) Program that he co-founded and co-directs with Karthik Raghunathan, MBBS, MPH. This novel research program facilitates rigorous observational research using population health methods (epidemiology, health services research, health economics/policy, and implementation science) to advance knowledge and improve patient health outcomes in the perioperative and critical care space. Funded through department, industry, foundation, and federal grants, CAPER is a cross-collaborative hub for research on methodological innovation, injury epidemiology, resuscitation, analgesia and nutrition, multi-organ dysfunction, learning health care, and health equity.

Federally funded research programs among CCM Division investigators span a variety of critical care topics, including acute kidney injury, nutrition, rehabilitation after critical illness, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, pneumonia, sleep, delirium, and host-microbiome interactions in critical illness, among many others. With a strong mentorship component, says Krishnamoorthy, “the division also serves as a training ground for medical students, residents, fellows, and junior faculty interested in research in critically ill populations.”

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have opened up a myriad of future possibilities in the critical care space. “It’s another tool in our toolkit,” informs Krishnamoorthy, highlighting how it can help the intensivist analyze large volumes of high-fidelity granular data, especially waveform data that is too complex for traditional statistical models. “We are going to see more of these innovative models for disease deterioration, risk prediction, and predictive analytics,” he adds, urging physicians to also use qualitative judgment and be responsible stewards of these models as they define and refine clinical decision support.

Meanwhile, high-quality care requires high-caliber care providers. Krishnamoorthy’s focus is on recruiting faculty with widely recognized expertise that aligns with the broad and diverse spectrum of critically ill patient populations in the ICUs.

“We continue to attract and retain top talent to fulfill our clinical mission,” says Krishnamoorthy, adding that national leadership positions in education and research allow Duke Anesthesiology Critical Care Medicine to build its brand as one of the leading programs in the country. “Top recruits not only want to contribute and help grow some of our areas of excellence, but we also provide a fertile ground for career development in almost every domain of critical care,” he informs, pointing to a strong mentoring culture to ensure a pipeline of recruiting talent.

Hashmi concurs. “As the fellowship director, I spend a lot of time interviewing applicants and recruiting both internal and external candidates to the fellowship. In general, residents tend to gravitate towards subspecialties where they have had the best experiences. The faculty and I are actively working to generate and maintain interest in ICU rotations and engage residents in education, such as grand rounds, lectures, and problem-based learning.”

In the face of a national shortage in critical care applicants, exacerbated by the pandemic that led to burnout in this high-acuity, high-stress environment of subspecialties, the division’s fellowship recruitment efforts have increased. Social media and the CCM website have been leveraged to showcase the critical care fellowship.

On offer are carefully curated didactics, simulation, echocardiography, and research experience during training. Fellows learn from faculty with expertise in various streams of critical care as they rotate in the SICU, CTICU, MICU, Neuro ICU, Duke Regional ICU, and various elective rotations where they interact with providers outside their department. In turn, the MICU and Neuro ICU fellows rotate in the SICU and Duke Regional ICU to gain a more comprehensive experience.

Additionally, all critical care fellows, faculty and advanced practice providers are invited to attend virtual lectures, journal clubs and problem-based learning sessions. The virtual learning platform can be accessed by both faculty and trainees. And, the CCM Division invites experts from within Duke and nationally to collaborate on various aspects of critical care medicine.

Growing careers of faculty is also prioritized. “It’s not one size fits all,” says Krishnamoorthy, emphasizing pathways - research, education, and clinical operations - for faculty development and engagement with structured mentorship that supports and nurtures growth. “There are so many great established programs, like the ABLE Program, within our department and across the institution to help faculty in these domains. Faculty have different goals, and we really try to personalize their career development into how they want to see themselves grow.”

As clinical operations director, Mehdiratta shares Krishnamoorthy’s “big picture” view of operations across the critical care space focusing on strategic recruitment, creation of optimal work schedules for physicians, along with ensuring that transparency is maintained in professional billing and clinical documentation. He also keeps lines of communication open to help address concerns quickly and efficiently. “Listening to what people have to say is more powerful than telling them what to do,” says Mehdiratta. “I find it very satisfying when you can see a problem, make a plan, and then actually enact a change in real time to make a difference with our staff, faculty, patients and their families.”

Keenly aware of the issue of physician burnout, the leadership team has employed a four-point strategy to address this ongoing crisis, informs Krishnamoorthy. The first step is to recreate a feeling of community and encourage more in-person gatherings to “decrease depersonalization” caused by the pandemic. The second effort is to improve daily workflow and streamline scheduling to increase predictability. “In many of our ICUs, we have started to schedule our ICU time one year in advance,” adds Krishnamoorthy. Mehdiratta also emphasizes the importance of optimizing schedules for physicians, as well as respecting their non-clinical time and time away from work. Third, institutional resources, including Duke’s Personal Assistance Service and various programs, are also available to assist faculty and staff while maintaining confidentiality and privacy. Finally, and most importantly, Krishnamoorthy stresses the need to monitor signs of burnout and take preemptive measures. Division-wide surveys, in addition to ACGME and Duke Culture Pulse surveys, help keep them informed.

The shortage of critical care specialists is making the ICU leadership find creative ways to provide access to intensivists for underserved populations. According to Krishnamoorthy, the team is working on a plan with the health system to develop a proposal that would expand Duke’s consultative and collaborative reach across rural North Carolina. The plan involves the use of telehealth for local physicians in ICUs that lack intensivists in these underserved communities.

Undoubtedly, critical care at Duke is a service that requires an entire health care team, including bedside nurses, respiratory therapists, speech and language pathologists, physical and occupational therapists, dietitians, pharmacists, advanced practice providers, and physicians, to work cooperatively with a focused goal of improving critical illness outcomes.

It’s a job the CCM Division and its leader know well as they strive to innovate and stay contemporary by seamlessly merging detailed medical knowledge and best evidence-based practices with the humanity of critical care.